María Magdalena Campos-Pons with Joyce Beckenstein

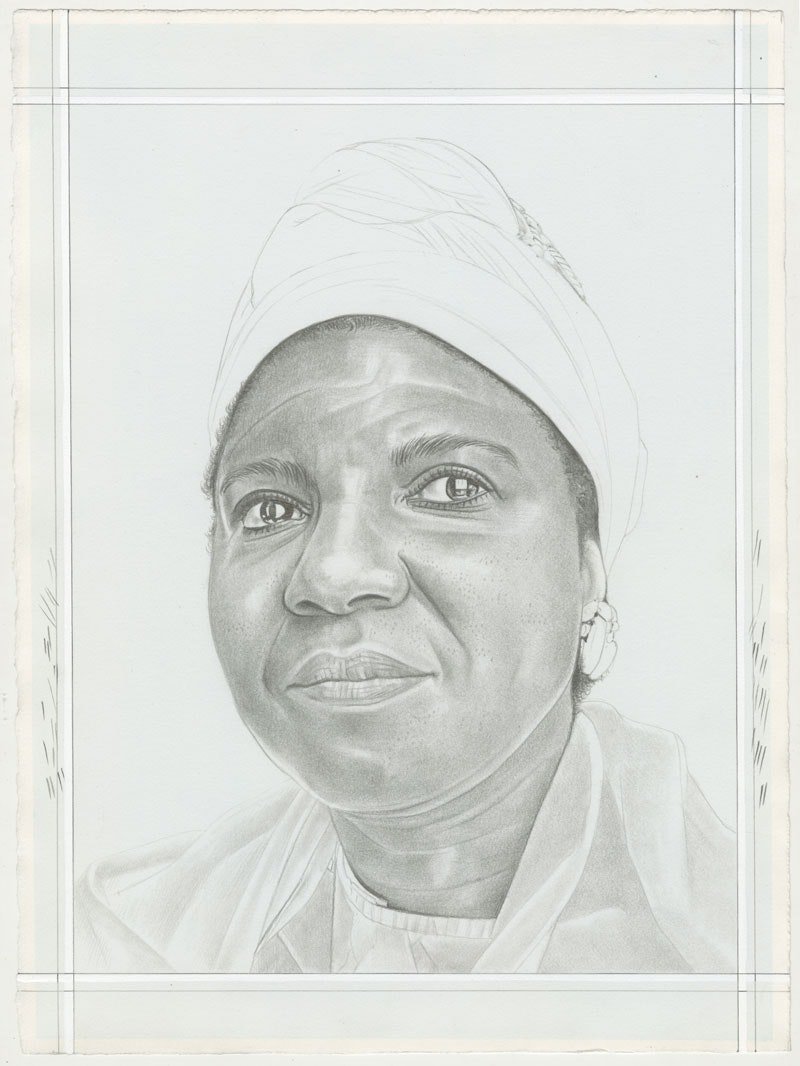

Portrait of María Magdalena Campos-Pons. Pencil on paper by Phong H. Bui.

Joyce Beckenstein

October 1, 2023

PDF

María Magdalena Campos-Pons (b.1959) came of age during an oxymoronic moment in Cuban history, a time when Fidel Castro simultaneously encouraged creativity and supported art education as he vigorously suppressed political criticism. The dictator clearly didn’t realize the power of form over didactic narration to make a point. Campos-Pons did. Her current exhibition, Campos-Pons: Behold, at the Brooklyn Museum, is the first survey of her art in New York. It invites us to witness her remarkable journey, a spiritual and physical odyssey that has landed her in Nashville, Tennessee where she today occupies the Cornelius Vanderbilt Endowed Chair of Fine Arts at Vanderbilt University.

The great-granddaughter of enslaved Africans and forced Chinese laborers exiled to Cuba, Campos-Pons makes art that distills the memory of generations of souls whose beliefs and dreams were subsumed by cultural compromises forced upon them. Gently weaving metaphors for human suffering and resilience through multi-media imagery—performance, installation, video, painting, sculpture, and drawing—she captures the human need to hold on to ancestral roots, to survive catastrophic upheavals and dislocations, and to ultimately rejoice through faith and hope. During our interview exploring the evolution of her four decade-long career she explains why she believes that “Art is our safe keeper. Our destiny keeper. The landscape of our journey.”

Joyce Beckenstein (Rail): When I visited your Boston studio in 2017, I noticed a potato plant winding its way up the wall. You laughed when I pointed it out, saying “It’s like me, a discardable plant with inner strength, something that arrived as an alien and had to adapt to a new environment.” Do you still identify with it and feel the need to adapt?

María Magdalena Campos-Pons: I do. I took the plant from the grounds around the Robert Rauschenberg studio in Captiva when I was an artist-in-residence there. Much of what I did then related to what was in the ground. They said it was an invasive plant that would grow anywhere, so I took it back to my studio, a new species in a new space. But the potato metaphor mostly relates to inner strength and the capacity of the plant to extend itself up… up… up, searching for light, for oxygen, and for potential.

Rail: What an apt metaphor for the multiple journeys you explore in your art. You first dealt with your ancestral memory of enslaved Africans, exiled to Cuba. Next came your personal flight from Cuba in 1991, to escape the oppression of Castro’s “special period.” You went to Canada, then to Boston. In 2017 you relocated again, this time to accept the Cornelius Vanderbilt Endowed Chair of Fine Arts at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. How have you stayed emotionally grounded throughout this odyssey?

Campos-Pons: There are many temporalities, a word I use to describe the ways I’ve experienced myself in the world: as a woman, a mother, a wife and divorcee, and as an artist. Each instance created a different learning experience peculiar to a time, place, or situation. I am grounded in my mobility, my understanding of transitions, and my flexibility to adapt to experiences that are not completely new, but that I need to explore by choice or necessity.

Rail: So, you are grounded in who you are, not where you are? You seem to express this throughout your practice, especially in your late nineties series, “When I Am Not Here/Estoy Allá.” You subtitled one of these self-portrait photographs Identity Could be Tragedy (1995–96), a reference to the ongoing diaspora that is part of your life.

Campos-Pons: That was the very first series where I put a title to my feelings and to my psychological and physical experience. I may be here physically but elsewhere mentally, so yes, I am grounded in who I am. That potato plant is a container for this concept. new specie in a new space.

Rail: You were always in a difficult place as a Black Cuban woman, even in Cuba where you were the only black woman student in Castro’s famed Instituto Superior de Arte. How did you get so strong?

Campos-Pons: I have been the “only Black person” so many times in my life, but I have lived more years in America than in Cuba, and there are so many productive things here. And I can’t leave out my family. One piece, Spoken Softly with Mama (1998), celebrates women and family, acknowledging them as a force of good. We were/are Black women inspiring one another. From them, I learned respect for the elderly and to have a profound respect for nature. But in talking about that, I want to emphasize that when it comes to these things I work from a dismantled archive.

Rail: What do you mean by a “dismantled archive”?

Campos-Pons: I am talking about the way who we are gets dispersed through cultural dislocation. There was no time—no luxury—to tell your story when you were working in the field from sunrise to sundown. So many things are lost or non-existent because we lack photographic and written documentation, and the lack of our people writing our historical narrative is part of the oppression. This archival absence makes it much harder for me to reconcile the history of who my family is and where I come from as a member of society. So, I am intent on exploring how we keep track of the time we live in. It’s a conversation of class and access that is poignant and present for me, and it is why I am centered on inscribing into the narrative of history a visual language that adds something and enhances the collective experience of the Black diaspora.

Rail: The power of faith drives this narrative. For example, in the series “The Seven Powers” (1992–94), you used carved boat-shaped wood-plank canvases for graphic depictions of body maps; stick figures diagramming the tight positioning of human cargo on slave ships from Africa. Each board is inscribed with the name of a Yoruba deity, suggesting that faith will in some way prevail, despite the horror. The series then goes on to include images of family members, and a performance by you connecting personal history with this epic collective experience.

Campos-Pons: Yes, the “Seven Powers” series is prayer and song celebrating cultural survival. But the story I tell about colonial people and oppressions mostly represents a period of locked energy for people with my appearance. Black people. Their lives disrupted. Their energies locked. But they are not gone, the energy is not lost. The potential is there, it is just a question of time and faith. And about those stick figures on the boat … I am thinking about bodies in geography and the temporary geographies we have created.

Rail: What do you mean by temporary geographies?

Campos-Pons: When I think about geography, I think about how we define who we are. If I don’t have my papers, I am an alien.

Rail: You deal with that in a portrait you painted of a woman you met in Italy at a police station when you went there to settle immigration issues.

Campos-Pons: Invocazione alla questura - Rita of Nigeria (2006) is a piece in the current Brooklyn Museum exhibition. I did this work in Padua, Italy where I met a Nigerian woman who made many trips to the police station to get her immigration papers. I started talking to her, thinking about the Black body in transition and I questioned her. Were we welcome, not welcome? I remembered her wearing a baseball cap, which in the painting I transformed into a traditional hat with African beads hanging from it, like a veil shielding the face. I put a bird on top of the hat as it is used in traditional Yoruba garments. It was a theme marking an engagement with Black bodies—marking the past and marking how we are still in transition in society. All the material in the work is from fabric I got in Africa, and the paper comes from products I purchased in Italy, things that were part of my everyday experience. This was my way of creating a conversation with tradition, about making Africans recognizable, and juxtaposing situations we encounter, such as staying in the country legally without being arrested.

Rail: Why were you afraid of that?

Campos-Pons: If you were a Black woman walking down the street, and you didn’t have papers….

Rail: Understood. I’m also beginning to better understand what you mean when you talk about the relationship between body and geography, and how you use that connection in your art.

Campos-Pons: The point is this: I am not an alien on this planet. I descend from people who inhabited this place early on. I’m a citizen. I belong to this present time, to this world as just one small entity in a complex universe. I could get into a lot of shit for saying all this, but it doesn’t matter. I am talking to you as I am feeling, thinking, and living, because what I am trying to do with art and words is to recognize humanity existing in an amazing garden with splendid variety. We were given an incredible brain to do extraordinary things in every curve and corner of this small sphere called Earth.

Rail: Are you saying that you think of yourself as a speck of nature embodying all of nature? That you want your art to transcend your specific cultural history, to underscore your presence, and that of your people, as part of a larger existence that we all share?

Campos-Pons: Yes, and this is also part of a visionary and futuristic outlook.

Rail: So then, “When I Am Not Here/Estoy Allá” is not just saying “When I am here in Tennessee I can also be in Cuba, Africa, or somewhere else.” It is saying, “When I am in ugliness, I am also in beauty.” Is that what you mean?

Campos-Pons: Yup.

Rail: This is probably a good time to talk about your position at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. Did you have reservations about moving to the South?

Campos-Pons: Being in the South, in Tennessee, forced me to think about the implications of being in this part of the US. I came to this new place, with its luscious garden on the Vanderbilt campus, but the garden and nature held profound contradictions. Black bodies hung from the kinds of trees that now shelter me. This cannot be forgotten.

Rail: I must say that when I first saw the work, The Seven Powers Come by the Sea (1992), with blatant, diagrammatic representations of enslaved people chained in their boats to their fate, I wondered how you’ve contained what I think of as mythic rage. I wonder the same as I hear you speak about walking among the flora and fauna in a garden in Tennessee, a state where Martin Luther King was assassinated in 1968. What I find most compelling about your art is your ability to temper hard reality with a soft touch, to acknowledge what is unspeakable yet abstract from it the beauty and the promise for humanity and the future.

Campos-Pons: I love that. Thank you for your words.

Rail: But the world is not a pretty place, today especially. Ghosts of the past walk through those gardens. How do you deal with that?

Campos-Pons: [Laughs]. Oh Joyce!

Rail: I never said I would make this easy, Magda.

Campos-Pons: I am grateful to hear you speak about beauty. I am a conduit for love and the healing power of beauty. Art is a love potion, and I am in a moment and time when I am focused on what I call venting power, the transmutable power of love. I am in Nashville, and it’s been a wonderful productive time for me. Every day I meet a stranger. Every day I speak with someone I do not know—on my way to school, at the university, in cafes, in the market. Every day I make this quiet performance by exchanging information with Jehovah’s Witnesses, students, homeless transients, and workers from many professions and trades. I engage with these strangers because it is important to know the materiality of people. They validate my sense of what the future can be.

Rail: Much like meeting the woman in Padua?

Campos-Pons: Yes. I want to do a piece to open myself, to make a meal and come back to what my grandmother and mother did; to talk to someone through a meal because I am thinking of the table as a place to negotiate and as a place of resolution. A table and a bed are not very different. They are very essential. They are two places to make peace, to come to agreement, to connect, and to communicate with love.

Unfortunately, many in our time do not have a table and a bed. I say all this because you asked how I arrived in Nashville, a place I came to, not as an innocent, or unknowing about history. It is a place that invited me as a means of reconciliation through a special dialogue with history. So, I am profoundly appreciative of the role that Vanderbilt asked me to play. The position I was given, the Cornelius Vanderbilt Endowed Chair of Fine Arts, bestows a space for agency, something I regard with a great deal of commitment and responsibility.

Rail: What was the first piece you created after arriving there?

Campos-Pons: When I arrived at Vanderbilt there was a tree on the grounds about to be cut down after a storm. I negotiated with the ground crew to bring it to the courtyard of the art department where I used it for my very first artwork in Nashville, a performance I did with students titled Sleeping Like a Log. It featured me sleeping on top of the log of the cut-down tree. I wanted to make the statement that all these trees have history. I was finding a connection with what was rooted here, a connection with the potato plant we spoke about.

Rail: This connects with the spirituality defining most of your art, and the way you embed mythic spirituality into your present environment, and beyond.

Campos-Pons: I must tell you a funny story about spirituality and my work. In 1994, I was invited to a house in Brooklyn, near Prospect Park, for a conversation with some interesting people in the arts. They were looking at me for some galleries in New York, and someone asked me to describe my work. I said, “it’s spiritual.” I observed eyes rolling. Nothing really happened from that conversation, except that I kept working. And eyes also rolled when people equated my work with surrealism, a genre which at the time was not of interest to the art world. I was dismissed as well for that. But I was dealing with a different dimension. When I call the ancestors, I believe they listen to me … they are with me. I’ve always thought of spirituality as material, something tangible.

Rail: So interesting that you seized as metaphor the image of a southern tree—a magnolia tree.

Campos-Pons: The entire series I’ve done here with the magnolia tree relates to spirituality. The tree is a witness, a metaphor for ecological and social history, our connection to nature and human endurance. Secrets of the Magnolia Tree (2021) symbolizes so much of what we’ve discussed. And the magnolia tree comes back every season bringing beautiful flowers; I have documented every transformation of its seasonal cycles. I feel I belong with it. Every time the magnolia blossoms, I blossom too. It is part of my soul. I share beauty with it.

Rail: You often refer to the “materiality” of people and the “materiality” of the spiritual, something we think of as incorporeal. How do you translate and connect these concepts through your choice of actual materials, particularly the way you use your body as medium?

Campos-Pons: At the end of the day, I am not interested in painting, sculpture, photography, drawing, printmaking, or performance art as a hierarchy of materials or disciplines. I imagine myself in the making of art: my body as a performative entity that releases energy too long locked within the Black body. It is an interpretive vehicle of communication, one that filters information past and present. All the while I ask myself, “How does this enlighten the future?” I care about this as a witness to my time. I mean my art to create a homage to this time for the future.

Rail: Let’s talk specifically about the body as an expressive element in your work. You incorporate your body in so many ways, using so many different processes. For example, in photographic works such as “Nesting” (2000) and “Freedom Trap” (2013) you use your own hair to send mixed messages.

Campos-Pons: Most Black women were reprimanded for wearing their hair in a natural way, so Black hair has much to say about Black history. In both the “Nesting” and “Freedom Trap” series I wrapped my head in fabric, hair, African beads … even tree branches to suggest both cultural and spiritual connections with the world. These “nests” and hair “cages” recall my arrival in America and starting a family. They often contain a wooden bird and are metaphors for so-called freedom.

Rail: It sounds as if the metaphors go beyond the cultural and spiritual, and here chronicle a time of life when you were a young married wife and mother. Do these works relate to the way many women in the early feminist days expressed conflicted feelings about their domestic and gender roles?

Campos-Pons: Yes. I was feeling that way, and there are a lot of notations about that time. In fact, I wrote a poem when I did the “Freedom Trap” series, but I can’t find it.

Rail: You also explored variations of Black skin, notably using a Polaroid camera, a new media for you when you came to the US. Tell us how and why the subject of skin color merged with the Polaroid image, and how that in turn influenced your later work.

Campos-Pons: The history of photography documents some problems when it comes to the way light registers Black skin tones. If we were photographed together, your image would have more details, mine would have less clarity. Polaroid helps to correct that. With Polaroid 7 I could capture skin tones in a more beautiful way. Early on, I was privileged to work with amazing Polaroid people, Tracy Storer at MassArt and John Reuter in New York, very passionate and patient individuals who fell in love with all the craziness I brought to the studio. For example, Polaroid allowed me to improvise and use the technology, not to document, but to construct different scenarios in the moment, as they occurred to me. I was able to spontaneously invent a series of stage sets as each new picture was taken. That is how I was able to create photographic series, such as “Nesting” and “Freedom Trap,” so that the individual images connected in a filmic manner. There was lots of improvisation. This process allowed me to construct a series of still performances that relate to the complex narratives one finds in films and videos. I think my approach to photography indeed derives from my love of films.

Rail: You also focus on eyes, using photography, painting, and glass. I was particularly struck by The Right Protection (1999), an early Polaroid work which is now in the MoMA collection.

Campos-Pons: This work, a nude photograph of me with eyes painted all over my back, is about my parents telling me that I have “eyes” on my back, a sixth sense. I am so grateful to them for saying that because it gave me my clearest understanding of spirituality, the capacity to see what is beyond that which you can physically see. Your entire body is alert. And it’s funny you bring that up now, because I am now working on a piece with an old body, one that gained weight over time and that has accumulated fat. I want to do a picture of all women in this state because we are all beholders who can see beauty through what seems ugly. An old body can still see very well.

Rail: You touch on the title of your current exhibit, Behold. Talk about the two “eye” works in that exhibition.

Campos-Pons: I start with the idea of seeing beauty in truth in Voyeurs and Beholders of… (2004). This photograph represents every eye color and shape, each eye shedding tears. I am thinking of formative moments, seeing ugliness, and needing to come to terms with everything you see that is wrong in the world. You can cry, but you can cry through elation because there is space for beauty and optimism. The glass eyes in Mobile #1 (2021) expresses this: they are like butterfly eyes, a spiritual connection protecting these delicate creatures from predators.

Rail: Glass is such an important material for you. It makes a compelling statement in what is arguably your most iconic installation piece, Alchemy of the Soul, Elixir of the Spirit (2015). How did your work with glass evolve?

Campos-Pons: I always thought of glass as vulnerability. I did the first glass work in the late eighties, about going through a glass door. It is fragile, yet strong, a blockage but you can go through it. In Spoken Softly with Mama I made cast glass irons, heavy objects domestic women sweated over. They served as prisms for people who were entrapped, a homage to all Black women who toiled though they were gracious and elegant. Alchemy of the Soul is a conversation with architecture as memory. It is about the production of rum in Cuba, a product realized from backbreaking slave labor. The glass tubing represents the rum-making machinery. As you enter the room you are intoxicated by the smell of rum going through the glass tubes. Gradually the aroma turns rancid. It is about sweetness that came from human suffering.

Rail: Your later works become more abstract, many of them relate to water and its myriad associations with nature, survival, and journeys. At the same time, the meaning of these works transcends Afro-Cuban diasporas to embody the plight of others suffering in today’s world.

Campos-Pons: Water is everywhere in my work. Much of it is related to my time in Cuba, but other pieces, such as Elevata (2002) drinks from the Renaissance and my time in Italy, as well as my travel back and forth to Cuba. Another series, “Un Pedazo de Mar” (2019) was inspired by tragedies: incapacitated and dead slaves thrown overboard by slave traders; refugees today trying to reach other shores in vulnerable vessels, headed to places where they are apt to be shunned. So many bodies lost at sea. In my art I want them to re-emerge from the depths of the ocean, what I imagine to be the uterus of the Earth, and to then paddle towards a new destination. Is this not the source of the Black and Brown diaspora? There is the buoyancy of water, and my references to water are about buoyancy and a place where you can float free in the universe. It is about the power of survival.

Rail: How have all these works we’ve been speaking about evolved in your most recent performances?

Campos-Pons: Many ideas continuously thread through my work: I did my very first performance at age eleven. My early sculptural piece, Chastity Belt (1985) was about the female body as a carrier of power. This is manifest in a video performance, Initiation Rite/Sacred Bath (1991), a performance video that was like a rite of passage for me because it connects with my grandmother, a Santerían priestess. She taught me Yoruba beliefs and traditions. This video represents cleansing rituals that are passed down through generations of women, and ceremonies involving the body as a conduit for energy, the essence of so much of my work today.

Rail: Cleansing ritual, the power of Black women, and the breaking through of political barriers that kept Black people from art institutions coalesce in your powerful 2014 performance in the rotunda of the Guggenheim Museum.

Campos-Pons: In that performance, Habla La Madre, I wore a dress with foam rings to surround my body with a representation of Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture. I personified a Black figure, an artist—not a frequent presence in white-dominated art spaces until recently. Like Frank Lloyd Wright, whose architecture merged with water and nature, I used the fountain at the Guggenheim to express women’s connection with a life force. In the performance I summoned the Orisha gods to claim a Black presence within the white space of an iconic museum.

Rail: In 2022 you performed When We Gather at the National Gallery of Art. This performance, celebrating all women’s achievements, features women dressed in white, chanting “this house needs cleaning,” a message that hurls all the themes we’ve been discussing directly into our present lives.

Campos-Pons: The idea for that piece occurred to me in a dream. It had to do with human connections and the way we use art to create interactions. The chants in this performance relate to the pollution in society, corruption, the trauma of a pandemic, and the political ruptures in the world. So yes, this house still needs cleaning. There is a lot more work to do.