Artists Whose Vitality Flows From the Streets

Artists Whose Vitality Flows From the Streets

By HOLLAND COTTER, JUNE 16, 2011

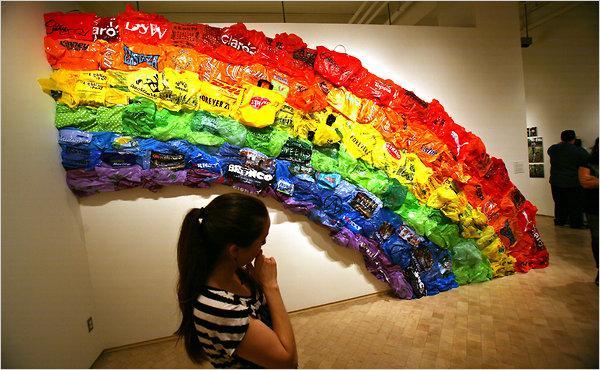

El Museo's Bienal: The (S) Files 2011 The show, at El Museo del Barrio, surveys new Latino, Caribbean and Latin American art and features Alberto Borea's “Rainbow,” made from plastic bags.

Credit: Librado Romero/The New York Times

Because of a long renovation of El Museo del Barrio’s Fifth Avenue building, four years have passed since the museum’s last “bi-annual” survey of new Latino, Caribbean and Latin American art. As if to make up for lost time, the new edition is the biggest so far. It includes work by 75 artists spread over seven shows in four boroughs, with the main event at El Museo itself.

The title for the whole shebang is “El Museo’s Bienal: The (S) Files 2011,” with the S standing for “Street,” as in street art. It’s a baggy theme, encompassing everything from graffiti to junk sculpture to painted cityscapes, and some of the work has problems with focus. Yet taking the street as a subject opens the possibility of at least thinking about other subjects, like money, and the lack of it.

Although the market keeps crowing about how auctions and fairs are booming even in a ruinous economy, the exhibition catalog points out that the average artist is having a tough time, scrounging for the odd job, for a place to show, even for materials — all things that the street has helped provide in hard times past. The show itself also suggests an alternative definition of “average artist.” Scan the résumés of participants in mainstream roundups like the Whitney Biennial or “Greater New York,” and you’ll find lots of Ivy League M.F.A.’s and out-of-the-gate Chelsea debuts. Collectively the artists in “The (S) Files” tend to have somewhat different credentials in biology, sociology, mathematics and telecommunications, earned at institutions that range — and I restrict the range to New York City — from Columbia University to Apex Technical School.

Visitors to El Museo del Barrio look at “Honest George” (2009), a painting by Lee Quinones, who is one of 75 artists featured in “El Museo's Bienal: The (S) Files 2011.”

Credit Librado Romero/The New York Times

As for prestige galleries, some are represented. But far more of the artists here show in places like Splatterpool, Helenbeck, TT-Underground, Buzzer Thirty, Monkeytown and Sacred, not to mention in hardscrabble alternative spaces like Tribes on the Lower East Side and Taller Boricua in East Harlem, a few blocks from El Museo.

In short, the “The (S) Files” confirms what should be obvious but rarely is in the art world: there are scads of artists out there with careers and lives that don’t, whether by chance or by choice, revolve around a few square blocks of mid-Manhattan art real estate. At the same time another truth is demonstrated: In a highly competitive market that turns art schools into art mills, a lot of art, no matter where it comes from, looks like a lot of other art everywhere.

The show starts off with a pair of cityscapes that give contrasting urban views. The first is a panoramic mural — part painting, part collage, part sculpture — by the young Brazilian Priscila de Carvalho, of tiny figures dwarfed by towering buildings and a toxic-looking sky. The second is a set of photographs by Daniel Bejar, a Bronx native, documenting a kind of guerrilla project that had him replacing regular, multicolored New York City subway maps with new ones featuring boroughs colored entirely green to evoke the pristine forestland the city once was.

From this we move to another history, that of a specific urban art, graffiti — or rather to recent work by three of its pioneers, all immigrants: Lady Pink (Sandra Fabara), born in Ecuador; Mösco (Alvaro Alcocer), born in Mexico; and Lee Quinones, born in Puerto Rico. (A fourth artist, Cope2, a k a Fernando Carlo Jr., born in New York City, has a piece in El Museo’s cafe.) All these artists started painting in the streets as teenagers in the 1970s and ’80s but have since shifted much of their activity to the studio.

Mr. Alcocer transmutes a tradition of aerosol calligraphy into fluid oil-and-acrylic abstract paintings. Mr. Quinones keeps the anti-authoritarian impulse of old-style street art alive in a figurative painting, framed as if for a baronial hall, of a wolf dressed in a red hunter’s jacket and stalking the viewer through trees with dollar bills for foliage.

Ms. Fabara’s “Women Breeding Soldiers,” with its images of embryos and falling bombs, cuts right to the political chase and is painted, at least in part, on the wall.

Some younger artists are tackling topical content in direct ways too. Geandy Pavón, who was born in Cuba, has a masterly trompe l’oeil portrait of Barack Obama in the show, or rather a painting of the president’s face as if seen in a crumpled-up photograph. Last month, however, Mr. Pavón took portraiture straight out to the street when he projected an image of the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei onto the facade of the Chinese Consulate on West 42nd Street in Manhattan.

Mr. Obama appears again in a sequence of paintings by Joaquín Rodríguez del Paso, where his melting face is paired with the image of a dish of vanilla ice cream dripping with chocolate sauce. Race, as fiction and reality, is one of the show’s recurrent subjects. In a photographic narrative by Rachelle Mozman, one Latin American actor — the artist’s mother — plays the roles of aristocratic twin sisters, one light-skinned, one dark, as well as a family maid.

And in a series of silhouette self-portraits, Firelei Báez, who is Dominican by birth, simultaneously asserts and cuts through what she calls an Afro-Latina identity. Her hairstyle changes from portrait to portrait — from curly to straightened, and so on — but her staring eyes, her only visible facial features, remain the same in each picture.

Ethnicity as a performance is at its most theatrical in Irvin Morazán’s fantastically costumed performances, in which he wears towering masklike headdresses that mix references to pre-Columbian and contemporary hip-hop cultures. In a 2009 video made in his homeland, El Salvador, Mr. Morazan wears his “Ghetto Blaster Headdress” as he presides, like a Mayan potentate, over a break-dancing display.

The headdress, on view in the gallery, is basically an assemblage of found odds and ends: a tape deck, feathers, tons of gold chains. And the show — organized by Rocío ArandaAlvarado, Trinidad Fombella and Elvis Fuentes, all curators at El Museo, and a guest curator, Juanita Bermúdez — devotes quite a bit of space to work made from recycled objects and materials, with uneven results.

Alberto Borea makes something purposeful — a wall-size diversity rainbow — from hundreds of plastic shopping bags.

But Abigail DeVille’s grotto of amassed found paper and plastic just looks like a pileup of debris, despite a highfalutin title. In the end the most satisfying work is the most visually unassuming: a beautiful abstract wall relief made of stretched inner tubes by Adán Vallecillo; an ingenious sound installation by Thessia Machado, with two turntables tripping off miniature percussive devices; three small object-video sculptures by Marcos Agudelo; and Jessica Kairé’s stuffed-and-stitched soft-sculpture weapons: like morally slippery toys, they render aggression harmless but also make it O.K.

I like the two moody photographic self-portraits by Sol Aramendi, an artist who came to New York from Argentina several years ago and created a photographic program called Project Luz for new immigrants to the city. And I like the fact that many of the exotic props surrounding her in her pictures were borrowed from a friend, the artist Juan Betancurth, who has an installation that doubles as a performance space near the entrance to the exhibition.

Born and educated in Colombia, Mr. Betancurth describes his performances as being inspired by the lives and deaths of Roman Catholic saints; his stagelike installation, filled with mementos he associates with his mother, has the subdued air of a shrine. To some degree his work is “Latin American” in a way that’s unfashionable in these supposedly post-identity days, when everyone is being urged to leave geography and ethnicity behind.

Some of the artists in this show simply don’t do that, nor does the show itself. Is this a problem? Not at all. As long as the names that flash across the global art world radar continue to be generated by a blinkered Euro-North American art establishment, exhibitions with ethnic handles likes “The (S) Files” will remain a practical necessity.

So will institutions like El Museo del Barrio, which is not attached to a “barrio” at all, yet continues to serve an indispensable role as a showcase for Latino art in this Latino city, which otherwise finds little place for such work. (And, by the way, to get a clear sense of the intense social and psychological conflicts that still keep identity politics on the boil, you need only study this institution’s fraught history.)

Of course there are other reasons for savoring El Museo and its biennial: namely visual and intellectual stimulation, which promises to be multiplied several times in the months ahead as “The (S) Files 2011” gradually opens at other locations: Socrates Sculpture Park in Long Island City, Queens, on Sunday; Lehman College Art Gallery in the Bronx on Wednesday; the Times Square Alliance in Manhattan on July 14; the Northern Manhattan Cultural Alliance on Sept. 13; and the BRIC Rotunda Gallery in Brooklyn on Nov. 9.

“El Museo’s Bienal: The (S) Files 2011” continues through Jan. 8 at El Museo del Barrio, 1230 Fifth Avenue, at 104th Street, East Harlem; (212) 831-7272, elmuseo.org. A display sponsored by the group Chashama continues through Friday in the windows of the former Donnell Library Center, 20 West 53rd Street, Manhattan.

A version of this review appears in print on June 17, 2011, on page C25 of the New York edition with the headline: Artists Whose Vitality Flows From the Streets.